Today we’d like to introduce you to Claudia “Aziza” Gibson-Hunter.

Alright, thank you for sharing your story and insight with our readers. To kick things off, can you tell us how you got started?

I was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, to two very creative parents with a healthy respect for art. My father built everything. He was always renovating our family home and building model airplanes. Our home in Philly was unique because he had different ideas about form and function. He was completely untrained except for sheet metal classes he took as a young man. My mother, Jessie Gibson, was a homemaker. Later in life, she returned to school to get her bachelor’s and master’s degrees. Her dad, Irvin Thornton, was something of a curator for The Pyramid Club, a social club for prominent Black professionals in the city. He would visit area artists’ studios, requesting work arranged in a gallery in the club. He would often take his son, Irvin Thornton Jr., who later became a professor of art history at Cheyney State University, with him on his studio visits. He also worked at an auction house during the great depression and had access to sculptures, oriental rugs, and other items auctioned by wealthy people. I give this background to explain my parent’s interest in visual art. As a child, I had African masks and small sculptures of Black people in the house. My mother had inexpensive reproductions of Gauguin’s images of brown women dressed in bright colors lounging in their beautiful Tahiti homeland. She wanted my brother and me to be surrounded by images that would inspire our understanding of ourselves as Black people. They encouraged us in every way that they could. My brother became interested in writing and movies, while I was initially interested in art. We had something of a small recreation center, The Lee Cultural center, where I could spend my entire Saturdays in art classes. I attended the Parkway Program, an experimental high school that gave me access to PCA, now the University of the Arts. There I studied anatomy and went on to Tyler College of Art. Confronted with the visual culture wars that go on in art colleges, I decided to transfer to Temple University’s main campus, where I could take classes in Black Studies.

I took a Black literature class under Professor Lee, who introduced me to DuBois and changed my life. There, I read the New Negro by Alain Locke, a book that struck me at my core. I searched for a black aesthetic, and Dr. Locke’s writings inspired me to continue my quest. Having seen the work of Martha Jackson-Jarvis (she was transferring to Tyler from Howard University), I knew where I wanted to take classes next. However, it took me several years of teaching to raise funds to take a few courses at Howard University. I planned to take 15 credits and return to my position at a higher salary. At Howard, I both blossomed and declined. I wrote plays, poetry, comic strip artist, printmaking, drew, and poked my head into every department. Professors Jeff Donaldson, Winston Kennedy, Al Smith, Winnie Owens, and Edgar Adewale Sorrells were powerhouses filled with new concepts, techniques, and aesthetic possibilities, which they shared generously. I was blown away by the young black men and women that populated them. I was overwhelmed by the potential I saw, and my understanding of who and what I could be led me to become unfocused, but looking back, this self-discovery was necessary. I decided to give up my position in the Philadelphia school system, stay at Howard University, and focus on earning an MFA. I met my husband, became pregnant, and we moved to New York for him to continue his studies in medicine.

New York was difficult. I was a new mother, in a new place, unconnected to the art scene. When our son turned three, I started attending Harlem Studio Museum programs. While in New York, I completed my MFA and received a fellowship from the Bronx Museum of art. I joined Where We At, a Black Women’s artist collective, and began exhibiting again where We At had an exhibition titled Joining Forces with Black male artists. My partner for this wonderful exhibition was Kerry James Marshall. My studio was on 125th Street, and I shared it with Charles Burwell, who created beautiful works on paper using layers of crayon marks. David Hammons was on the first floor working on his elephant dung sculptures (my son was most impressed!). I worked as an academic advisor at Parsons School of Design at the time, attempting to balance artmaking, a job, and mothering.

We returned to Washington DC with our son and new daughter in 1986. I began a greeting card company, which allowed me to nurse her, and when my baby became a toddler, I began teaching first in the public school system and then at area universities. They include Howard University and Bowie State University. Along with PLANTA Reeder and Viola Leak, we gathered artists. We began what was to become Black Artists of DC, an organization of artists living, working, or being educated in Washington DC. This multi-generational organization offered education and opportunities to exhibit and support one another as their careers developed. Our members included: Michael Platt, Amber Robles -Gordon, Akili Ron Anderson of AFRI Cobra, Jamea Richmond-Edwards, Stan Squirewell, and many more. The critiques were hothouses for growth and a deeper comprehension of the thinking behind the work.

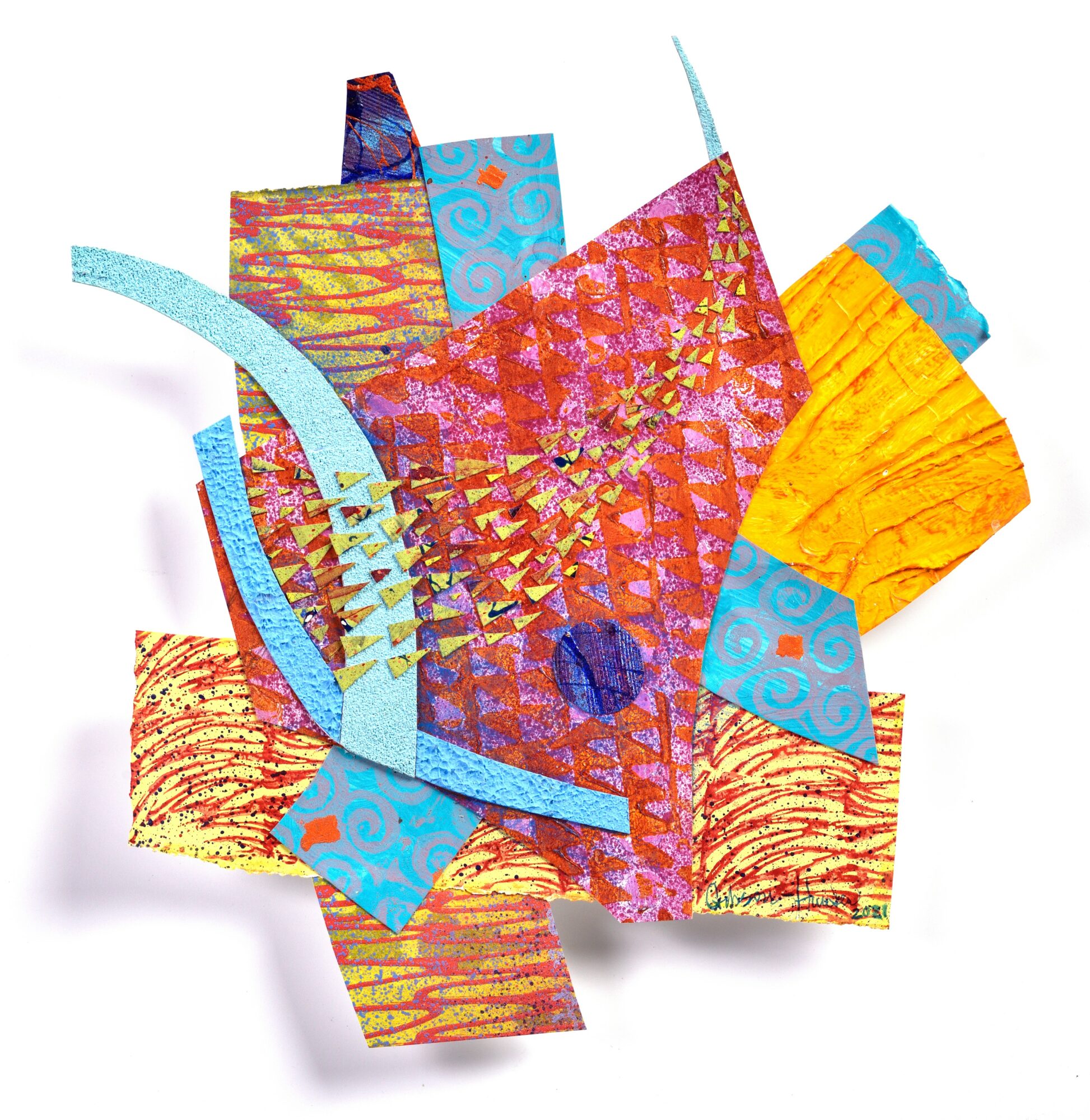

My work evolved from printmaking back to painting to combining painting, printmaking, collage, and papermaking. It has moved from figurative to completely nonfigurative to combinations of the two. Presently my work is abstract. Color, form, texture, and pattern are my tools to express the boundless possibility of people of African descent. My lens is ever-evolving

Ms. Gibson-Hunter was awarded the Individual Artist Fellowship Program Grant from the DC Commission of the Arts and Humanities in 2014, 2006, 2018, and 2020. Her work has been exhibited nationally and internationally. Her work can be found in the Washington DC Art Bank collections, the Liberian Embassy, Montgomery County, Maryland, and other noted collections. She completed two public commissions for Washington, DC Department of General Services. The Wall of Unity (2017) and ANCESTORS (2019) are both in Washington, DC, public schools. In 2019 Aziza was a Pyramid Atlantic Denbo Fellow. She is currently a cofounding member of Black Artists of DC, STABLE, a DC arts community, and WOAUA, Dandelion, and THOUGHT, three Black women artists collectives. Ms. Gibson-Hunter has a studio in Washington DC.

Can you talk to us about the challenges and lessons you’ve learned along the way? Would you say it’s been easy or smooth in retrospect?

No, it has not been easy, but it has been remarkable. The lessons, the creative people, and the sharing of one’s self and ideas through art have been priceless. When a person of color enters an art school, it can engage the student in a very serious culture war. The school is fighting to impart its sense of aesthetics, art history, and visual culture. Depending on the student’s exposure to other ways to think and see and their willingness to question and confront the dormant narrative, it can get pretty nasty. I have experienced this culture war and seen it attempt to destroy creative Black minds. As a woman and a mother, the challenges are many. Sheer determination and tensity are essential even today.

As you know, we’re big fans of you and your work. For our readers who might not be as familiar, what can you tell them about what you do?

I refuse to settle in and limit my growth, so my work has shifted over the years. This can be problematic because it is difficult to attribute my work to a “brand.” I love seeing the development of my work over the years. There are shifts in beliefs, perceptions, and techniques. I am alive; my work is always growing. Currently, my work combines painting, collage, printmaking, and drawing. I see my practice as a 21st-century one in that my work pulls from different media, creating lively juxtapositions. I see this in the sampling in music, the incredible speed of editing in today’s film editing, and in the young people’s dances that asymmetrically change pace and rhythm. There is this taking from and adding to create something different. It is as if we are all attempting to create something beyond what is. I understand this need. We human beings have disappointed ourselves. I believe humanness is incredibly awesome; we have not asked the best of ourselves. In my most recent work I am imploring that we reach higher, expect more, and know that we can be so much more than we ask of humanity. I enjoy the bright-eyed response of my audience.

Do you have any advice for those looking to network or find a mentor?

Mentoring has been very inspirational in developing myself as a human being and in my work. I encourage artists to see each other as colleagues that assist in developing one another. It was done for me, and I work to do the same for others. Artists need artists. Currently, the marketplace is arranged in the best interest of the collector and those who service the artist. This can change, and young people are using the internet to democratize the marketplace. Much more work needs to be done. We are the only art form where we are expected to pay to have our work consumed (viewed). This keeps us financially hog-tied in this system that we are currently in. The cost of art school is astronomical, and too few experience the opportunity to make a return on that investment through our art. Something needs to give here.

Contact Info:

- Website: gibsonhunterstudio.com

- Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/gibsonhunterstudio/

- Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/aziza.gibsonhunter/

- Twitter: https://twitter.com/ghunterstudio

Image Credits

Photos of art, John Woo (I do not remember the name of the artist that photographed me in front of my work, but he did give permission for me to use the photo.)