Today we’d like to introduce you to Lydia Yousief.

Lydia, we appreciate you taking the time to share your story with us today. Where does your story begin?

I was born in Bayonne, NJ, in the heart of a large working-class Egyptian community there. My father worked rehabilitating Rite Aid stores and had been here since 1983, and my mother, who had been a social worker in Egypt, moved to the US in 1989 and worked as a nanny and server until she was introduced to my dad in 1993. My mother had moved throughout the South before marrying my dad, and when my sister and I were born, my father wanted a desk job, and he was told, “The diversity quota has been met.”

Despite being one of the top performing managers for Rite Aid and loyal for several years in leaping from store to store to rehabilitate it from shoplifting and inventory issues, they didn’t want to promote him to a higher-paid, more stable position. So he quit and said he’d move South, where my mom had started. We moved to Tennessee in the summer of 1996 and have stayed there since. My father’s a dreamer and wanted to open up a restaurant. Before he had worked at Rite Aid, he had worked at several restaurants in New York City and found that he enjoyed cooking. But unfortunately, he couldn’t open up the restaurant and instead went back to rehabilitating stores in the South by buying a car wash from a fellow Egyptian in Nashville.

My parents raised us between our Franklin suburban home and that small store in Nashville and the Coptic Orthodox Church. In the 1990s, many Copts (Egyptian Christians) came to Nashville for ease of finding a job in a struggling hospitality industry; we revived that industry, transforming Opryland, BNA (Nashville International Airport), and the downtown hotels into what it is today. I grew up watching banquet servers, housekeeping staff, and laundry staff celebrate weddings, commemorate funerals and pray for our dead, and host baby showers; I saw joy and I saw transition and I saw love. Every house party and cookout and Sunday liturgy I grew up among my people.

A lot of my childhood informs my work today. I have been and am obsessed with my people. In college, I couldn’t find anything written about the large working-class Coptic people in Nashville who built this city, and so I wrote about it extensively because in between building this city, we also had lives worthy of being written down and told and carried close. I completed my master’s at the University of Chicago in 2019 and my thesis was about citizenship-making an identity for marginalized communities, like the Copts who are second-class citizens in Egypt and in the United States, who are treated both here and there as both invisible and hyper-visible.

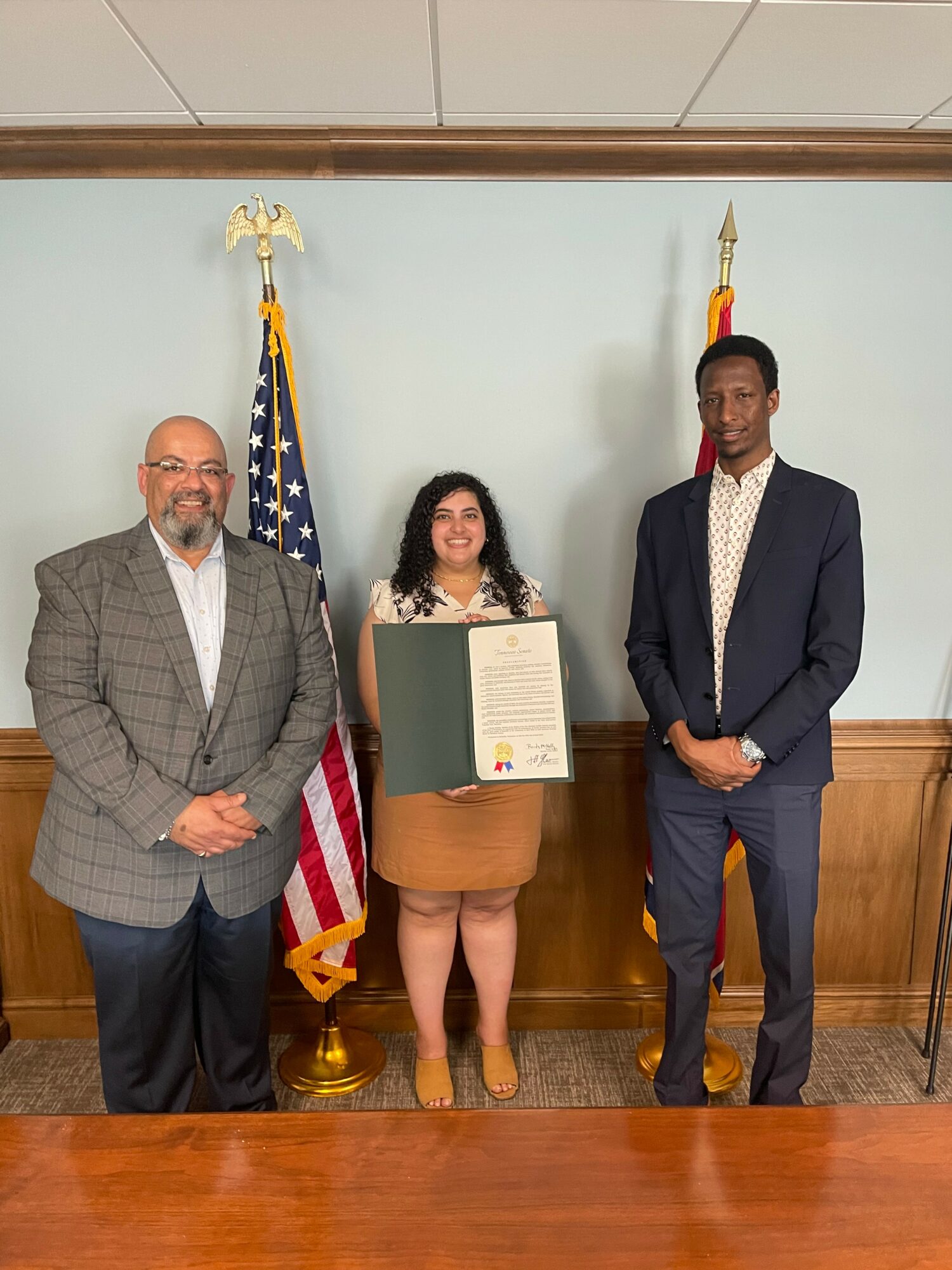

I founded, alongside Veronica Nashed and Erinie Yousief, my sister, an organization and we called it Elmahaba (in Arabic, Elmahaba means “unconditional/divine love”). Since then, I have continued to build the networks for Copts and other Arabs to build each other through each other.

Can you talk to us a bit about the challenges and lessons you’ve learned along the way? Looking back would you say it’s been easy or smooth in retrospect?

I’ve faced many obstacles in my life, yes, and I’ve also had a tremendous amount of privilege. Because my parents came to the US years before they had me, they were well aware of what it was like to live in this country and didn’t need to simultaneously learn how to live in a new country while raising children, which is what the majority of Nashville Arabs have to go through and it’s terrible.

Because I had parents who knew the systems vaguely, this saved me a lot of trauma in dealing with Western systems that weren’t flexible for newcomers. To me, this is crazy because, in Egypt, everything is made for the comfort of foreigners/non-Egyptians. But the US is one of the few countries, alongside many European countries, that is unfriendly about seeing another’s humanity.

In Egypt, things are translated into multiple languages, interpretation is a right, and the government is kind to those who don’t know the rules/law and is flexible that “you don’t know till you know.” This is the kind of atmosphere I’ve wanted to create at Elmahaba—similar to the Egyptian spirit—of being a helping hand, of being generous even when I don’t have much (or our budget isn’t large like others), of being a reliable support.

So in that, as going against the spirit of “pull yourself up by your bootstraps” theology in the US, I’ve faced many obstacles with other organizations and institutions who don’t believe kindness is the bedrock of humanity. In other ways, I’ve always struggled as an Orthodox Christian in the South where Protestantism runs deep. I remember, as a child, being called a heretic by so many other children because I wore a cross with a crucified Christ—I remember three specific occasions. The bullying led me to ask my mother to get me a cross that didn’t have a crucified Christ on it. I’ve faced extensive racism from teachers who thought I shouldn’t be put into honors class because “this was enough for someone like me.”

I’ve been told numerous times “You should be grateful for the opportunities this country has given you and your family,” denying the historical truth that for thousands of years my family has not left Egypt until now. When the Egyptian Revolution happened in 2011, I was bombarded with racist remarks of course. And looking back, I can’t believe as a child who hated her curly hair, her skin color, her eyebrows, her body, and her heritage, that I lived so many years hating parts of me that were beautiful.

A few months ago, I was in a meeting with a white MNPS teacher who told me that she was working on a project with her grandson about his culture and she said that she couldn’t think of anything, but that her students—the same age as her grandson—were describing Mexican dishes, Thai religious practices, Muslim holidays, Guatemalan drinks, Peruvian dresses, Arab dances, and she felt envious.

I wanted to tell her, “Don’t be envious. Those kids are probably going through the worst,” just like I was, hating parts of me that should have been celebrated, and in hating those parts of me, I also spent a long time resenting my parents, my community, my people, and suffered from that disconnection. But instead, I told her, “I hope they do celebrate those parts of themselves,” because I do.

Thanks – so what else should our readers know about Elmahaba Center?

Elmahaba started in 2019. We were three Coptic women who knew that, after 40 years in Nashville, our people still were denied access and resources. Despite Arabic being the third most-spoken language in Tennessee, most people in government and nonprofits do not make a concerted effort to support our large community.

What’s worse is that, because of the lack of resource distribution, our people started to become sectarian because Metro Nashville practiced engaging religious institutions like mosques and churches instead of centering secular spaces for Arabs. We knew our organization had to be secular and had to be multi-ethnic (Copts, Kurds, Moroccans, Shami peoples, Yemenis, etc.) and multi-religious and multi-lingual (in English and Arabic mostly but also able to support Spanish and Kurdish). So we started with direct programming.

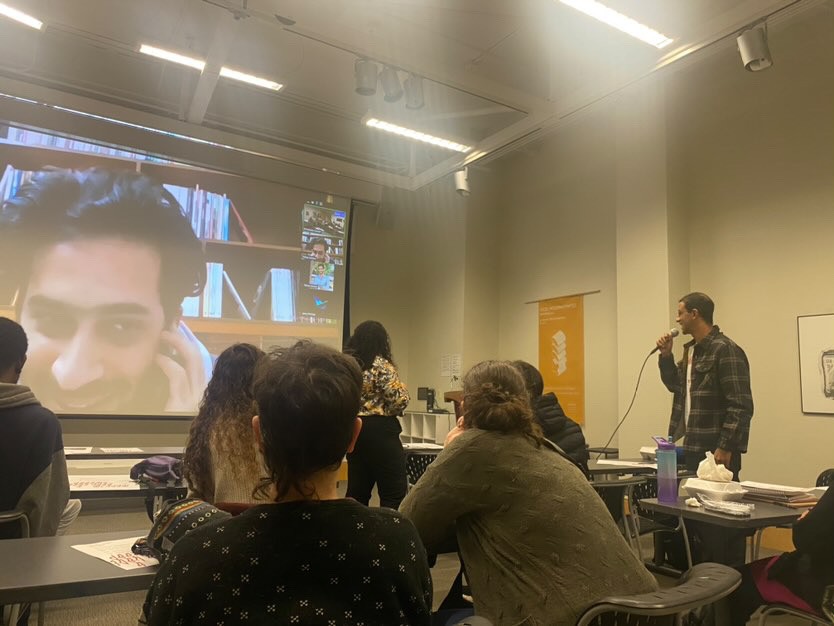

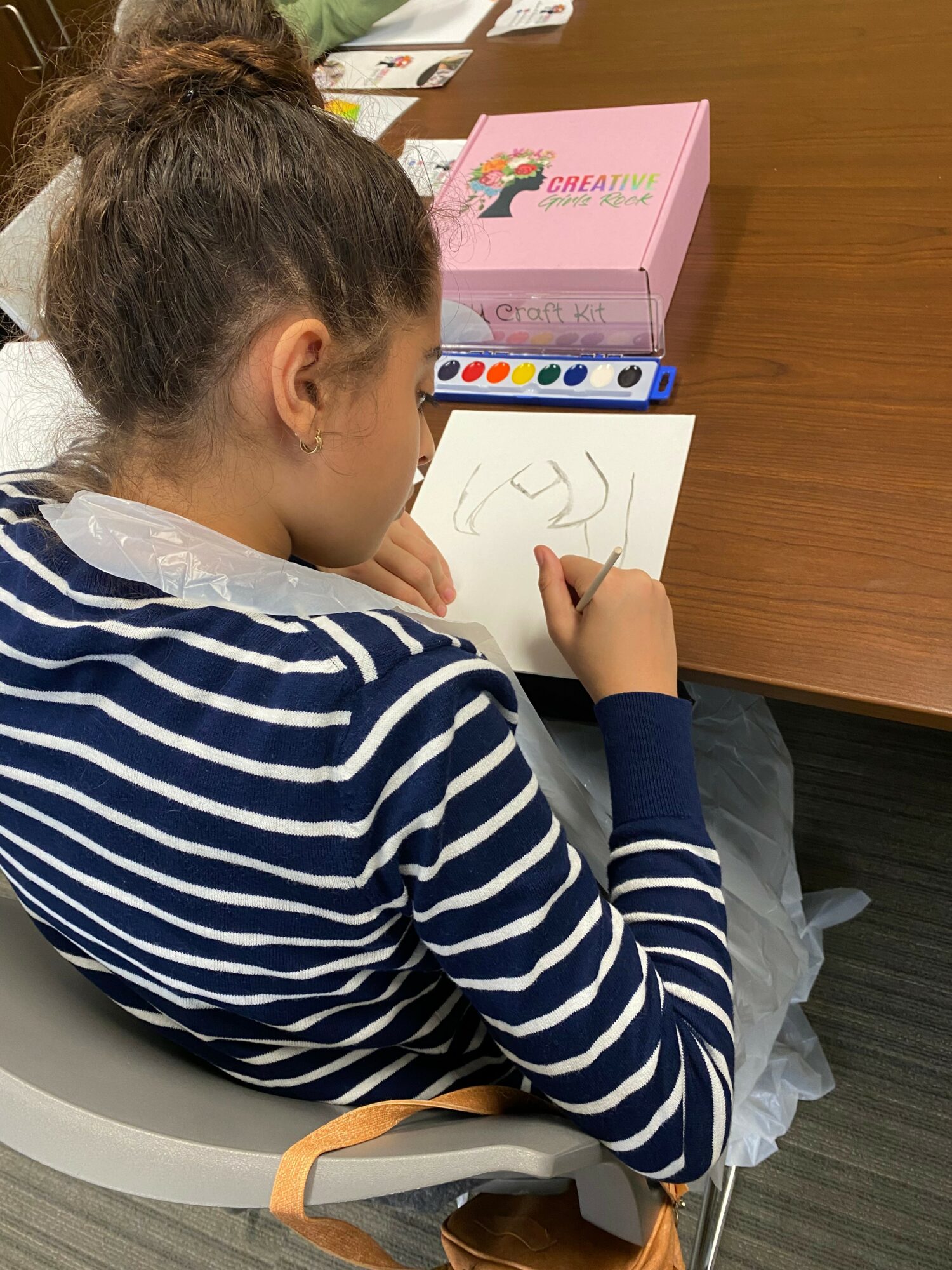

We have twelve direct programs which are: ACT Class, Tutoring, College Prep, Art classes, field trips, weekly livestreams, language co-op, ESL classes, mutual aid/monthly diaper bank, Arab Artists Guild, Justice School, Coptic Map of Nashville. We have two campaigns currently in 2023: we need the driver’s license test and study guide to be translated into the languages reflective of our people (so in Arabic, Kurdish, Dari/Pashto, Zomi, Chinese, Swahili) and also our community schools initiative.

We are proud that we are the only Arab-centered organization in Middle Tennessee, and that we are one of two secular, Arab-led organizations in Tennessee (Arab American Club of Knoxville being the other). We are proud that we are a small organization with only one staff member and four board members and about 75 tutors/instructors/volunteers, but we’re a powerhouse and a force, changing and raising the bar for acceptable community engagement and work.

We all have different ways of looking at and defining success. How do you define success?

I define success as contentment. I don’t think happiness is a single emotion too long for because sadness, anger, and desire are all worthy and important for long-term warmth. Therefore, instead of happiness, which is a mere emotion, I believe contentment is the most valuable human condition.

To be content with myself, my work and integrity, my family and friends, my body, my financial position, my goals, and my community are important to me. I try to achieve contentment by being present—being present during meetings or hanging out with a friend, taking a long walk, or asking for clarification instead of assuming the worst from someone. I believe the little things in life make life worth living.

Contact Info:

- Website: www.elmahabacenter.org

- Instagram: https://www.secure.instagram.com/elmahabacenter/?hl=ur

- Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/elmahabacenternashville/

- Youtube: https://youtube.com/@elmahabacenter696