Today we’d like to introduce you to Jim Massey.

Hi Jim, thanks for joining us today. We’d love for you to start by introducing yourself.

Fugitives beginnings:

I come from a long line of Tennesseans who believed in hard work, heritage, and the land beneath their feet. My family on my father’s side were among the first European settlers of Lincoln County, Tennessee, arriving in the late 1700s and early 1800s.

Some of my earliest and fondest memories are of our family gatherings at the old Massey farm — stories of our ancestors echoing through the fields, the smell of turned earth, and the sense that our roots ran deep in this soil. Those stories taught me who we were: farmers and educators who endured the Great Depression, who knew drought and hardship, who measured life in harvests and seasons, not years. Ours was a humble agricultural heritage, but one that carried pride — and resilience — in every generation.

My father was a man of many ventures, from farming to business, serving as president of the Tennessee Wine and Spirits Retailers Association for twenty-five years. But by the 1970s, like many small family farms, ours was struggling. One day, when I was about ten years old, I asked him why we didn’t sell our corn to Jack Daniel’s — after all, they were buying plenty of it.

He told me we couldn’t grow it cheap enough.

So I said, “Well, why don’t we just distill it ourselves?”

He laughed, shaking his head, and told me that American whiskey wasn’t profitable anymore — that distilleries were shutting down and Scotch was the better whiskey.

I shot back, “Well surely we can make it as good as they do in Scotland!”

To which he replied, “What do you know about it, you’re ten years old!”

That moment never left me. I knew then — in that exchange — that one day I wanted to make a great whiskey. One that would honor the legacy of the land where Tennessee whiskey truly originated.

The Spark Rekindled

Fast forward to the early 2000s. I came across an article about Lance Winters at St. George Spirits in California — a distiller earning national recognition for his bourbon. Reading it, I thought, If a guy from California can get that kind of acclaim for American whiskey, surely we in Tennessee can do the same — and do it in the place where it all began.

The problem was, at the time, Tennessee law still prohibited new distilleries.

Curiosity — and maybe destiny — led me out west to meet Lance. There were about fifteen of us at that early workshop — a small band of believers who would become the first members of what grew into the American Distilling Institute, now thousands strong. That experience lit a spark. But if I wanted to make whiskey in Tennessee, I’d have to change the law first.

I wasn’t entirely new to the halls of government. Years earlier, I’d worked for the Tennessee Senate Finance, Ways and Means Committee, so I knew my way around the Capitol — and I also knew what kind of entrenched interests I’d be up against. Brown-Forman, owner of Jack Daniel’s, had already tried and failed to pass legislation that would allow a downtown Nashville operation. They’d been blocked by a powerful lobbyist known around the Capitol as “The Golden Goose” — a man whose influence was as notorious as his nickname.

So how could we possibly succeed where Jack Daniel’s had failed?

As it turned out, the Goose’s largest client was the state’s liquor wholesalers — and their only customers were the retailers. And who had led the Tennessee Wine and Spirits Retailers Association for twenty-five years? My father.

It took one phone call to connect the dots — to explain how the craft distilling movement could benefit everyone: wholesalers, retailers, and farmers alike. The Goose honked about it, but we managed to keep his hands off our bill.

Changing the Law

From there, it was down to old-fashioned legwork. My friend Mike Williams and I spent weeks walking the marble hallways of the Capitol, meeting lawmakers, explaining that this wasn’t about big business — it was about heritage, agriculture, and economic opportunity.

We built a coalition that included local churches, trucking industry allies, and legislators who understood common sense when they heard it. Even Jack Daniel’s and George Dickel quietly supported the effort, though their lobbyists didn’t actively push the bill. We emphasized that we weren’t trying to rewrite Tennessee whiskey — we were trying to revive it.

In 2009, Governor Phil Bredesen signed the legislation into law, opening the door for new distilleries to once again operate in Tennessee. The photo from that day almost didn’t happen, but I convinced the Governor’s office that it was worth capturing. That big guy standing behind the Governor, grinning from ear to ear? That’s me.

Back to the Land

Changing the law was one thing. Distilling a great whiskey is another.

The next challenge was sourcing heritage grain — Tennessee corn and rye grown the old way. It sounds simple, but heritage grain doesn’t yield nearly as much per acre as hybrid varieties, and most farmers were understandably hesitant to plant it without guaranteed demand.

Luckily, I had friends who believed in what we were building. Singer-songwriter Jennifer Nicely had an ample supply of Hickory Cane corn grown sustainably on her family’s farm. And a dear friend and organic farmer, the late Alfred Farris, supplied certified organic corn and rye.

With that, the spirit of that ten-year-old boy — the one who once told his father he could make whiskey as good as the Scots — came roaring back. I was determined to make an authentic, heritage Tennessee whiskey that could stand among the best in the world.

The Lincoln County Way

One more challenge awaited: sourcing maple charcoal for the Lincoln County Process — the traditional filtration method that defines Tennessee whiskey.

Instead of buying it, I decided to make my own. Over a century ago, my great-grandfather had planted twelve sugar maple trees around the farmhouse, one for each of his children. Today, hundreds of their descendants grow across the Massey farm hillsides. I harvest only storm-damaged limbs to make my charcoal — real Lincoln County sugar maple, from the same soil my family has farmed for generations.

It’s free in cost but priceless in meaning. Every batch of whiskey I make passes through that charcoal, binding the spirit of our land to the liquid itself.

The Legacy Continues

Time and money are the twin challenges of any whiskey maker. It takes patience — and faith — to wait for the barrels to tell their story. But every day, I walk past those barrels maturing in the quiet, knowing that each drop represents something bigger than business.

This is about heritage. About reviving a legacy that predates Jack Daniel, rooted in Lincoln County soil and the ingenuity of Tennessee farmers. It’s about honoring the land, the law we fought to change, and the people who made it possible.

From a ten-year-old’s question on the Massey farm to the Governor’s signing pen, this journey has come full circle. We’re not just making whiskey — we’re reclaiming a birthright.

And the story of Tennessee whiskey is still being written.

Can you tell our readers more about what you do and what you think sets you apart from others?

The Difference:

I make whiskey that tells the truth about where it comes from.

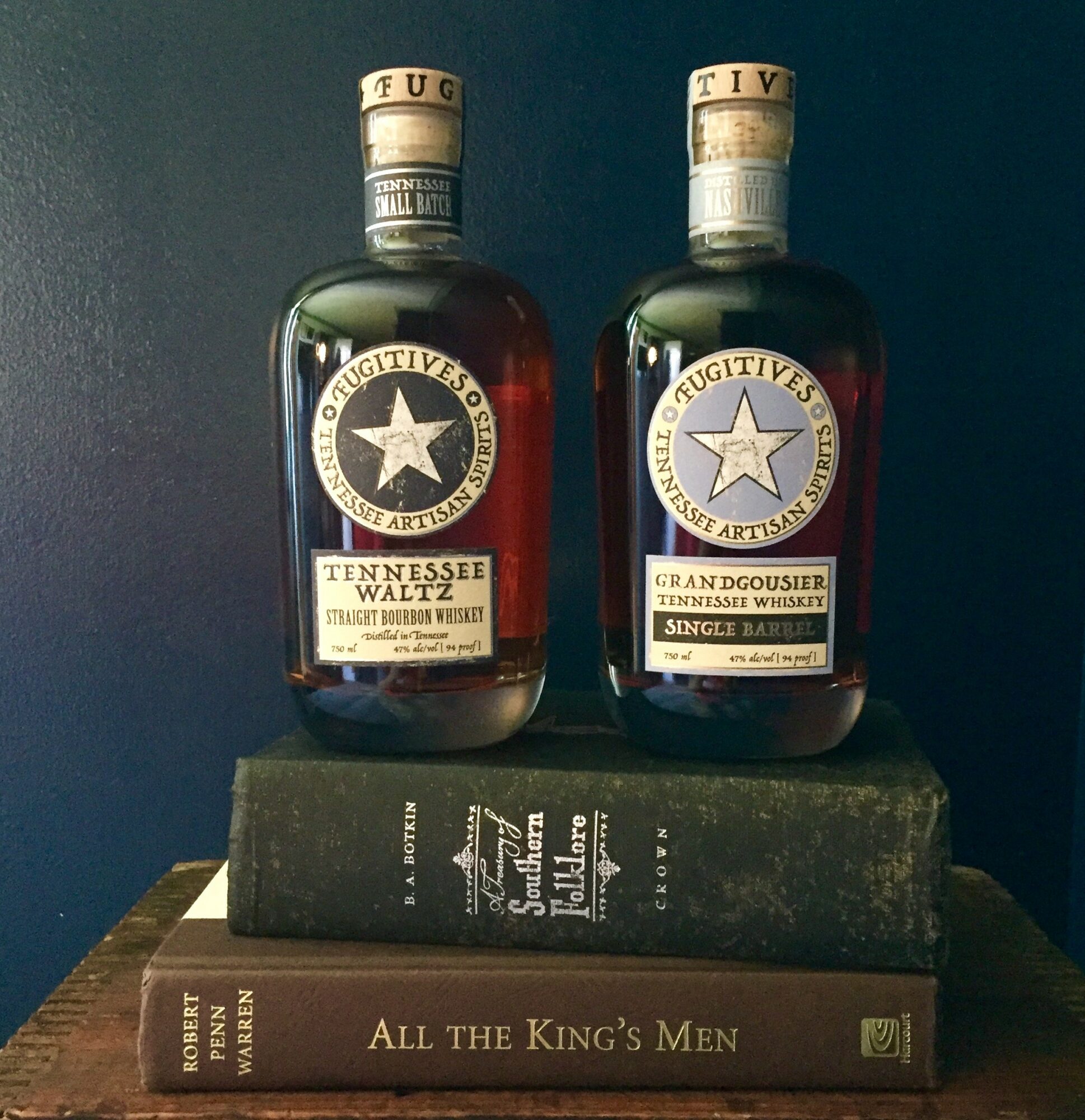

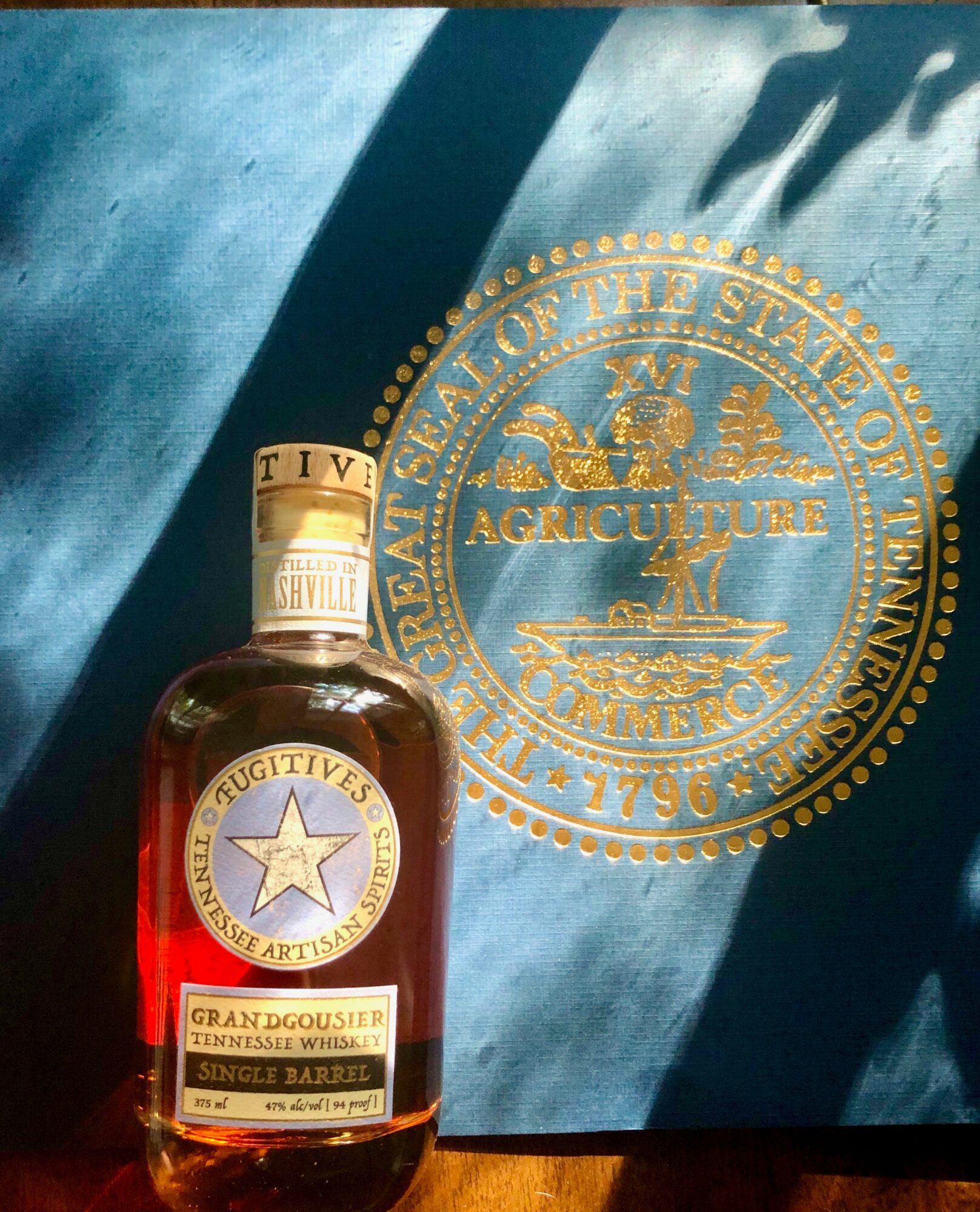

I’m the founder and distiller behind Fugitives Spirits, a Tennessee Spirits Company built to honor the original spirit of Lincoln County — the true birthplace of Tennessee Whiskey. I specialize in creating authentic, heritage-based Tennessee whiskeys using heirloom grains, local farmers, and real sugar maple charcoal from my family’s farm.

What I’m known for is reviving the original Tennessee Whiskey tradition — not just in flavor, but in spirit. I helped lead the legislative effort that made it legal again for new distilleries to operate in Tennessee after nearly a century of restriction, paving the way for today’s craft whiskey movement in the state.

I’m most proud that every drop of my whiskey comes from the same land my ancestors settled over two hundred years ago. The grains are grown by Tennessee farmers I know by name, and the sugar maple charcoal is made by my own hands from trees my great-grandfather planted. The corn we distill has a name, I like to point out in my best John C. Reilly voice “If they don’t tell ya what kinda corn they use to make their whiskey…, then they kinda do tell ya!”

What sets me apart is simple:

I don’t chase trends, sourced barrels, or marketing gimmicks. I chase authenticity — whiskey made with integrity, history, and place. I’m not trying to imitate Kentucky or Scotland; I’m working to reclaim what Tennessee whiskey was always meant to be: a spirit born from Tennessee soil, shaped by Tennessee hands, and true to its roots.

Who else deserves credit in your story?

Help along the way:

No one builds something like this alone. I’ve had help — real help — from people who believed in the dream long before the barrels were filled.

First and foremost, my best friend and life partner, Margaret, my wife. She’s worked double duty — managing her “real” job while handling everything from loading cases to doing the books — all while being an incredible mother to our children. There would be no Fugitives without her.

My business partners and investors, Darren Briggs and Martin Roberts, took a leap of faith and threw in on the dream. Mike Williams, one of my closest friends, was there from the very beginning — knocking on doors beside me in the Capitol when we were fighting to change the law and bring distilling back to Tennessee.

I’ve been blessed with mentors who shaped my craft and outlook. David Stewart in Louisiana became a dear friend through our work on the Alma Plantation rum project (Oxbow Estate Rum). The legendary Hubert Germain-Robin taught me to trust my own palate and showed me what it meant to age spirits the old-world way. Tom Sherman and the Sherman boys at Vendome have been invaluable resources, always generous with their expertise. Tom Mooney and my fellow “Big Bearded Guy,” Max Watman, continue to amaze me with their deep industry insight and authenticity.

I’m especially grateful to the Tennessee Department of Agriculture, who continue to champion small farmers and Tennessee’s agricultural heritage — their support keeps the roots of this craft alive.

And lastly, I want to honor the memory of Senator Frank Nicely and Alfred Farris — two men who stood at opposite ends of the political spectrum, yet shared a genuine love for Tennessee agriculture and stewardship of the land. Their common purpose reminded me that heritage and hard work can unite people beyond politics.

It’s been a long road, but it’s one I’ve never walked alone.

Pricing:

- Tennessee Waltz Whiskey $55

- Grandgousier Tennessee Whiskey Single Barrel $70

Contact Info:

- Website: https://fugitivesspirits.com/fugitiveshomepage

- Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/fugitivesspirits

- Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/FugitivesSpirits